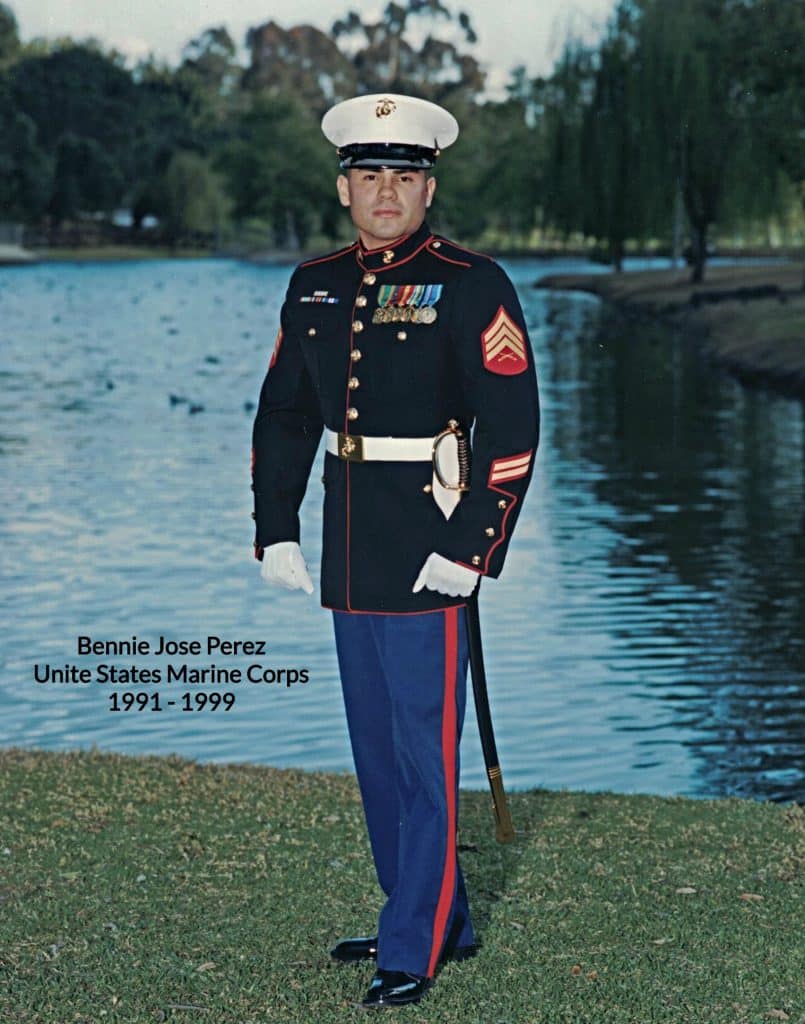

Editor’s Note: Bennie Jose Perez had dreamt of joining the Marine Corps from a young age. When he enlisted after high school, his dedication quickly began paying off as he climbed the ranks working his way toward his goal of a lifelong career in the Marines. Despite his commitment and hard work, a simple slip and fall would change the course of his life forever and force him to reexamine his career path and find a new passion.

When I was a kid, I would watch documentaries about the Vietnam War, and I kept hearing about the Marine Corps. My father would always tell me to change the channel because he didn't want me seeing the violence. I would change it, and of course, when he'd walk off, I'd turn it back. I was fascinated by the things they did and how heroic they were. As the years went on, my thought process continued to evolve and my admiration for the Marine Corps turned into appreciation. By the time I was 14, I was asking my mom if we could stop by the recruiting office. She would look at me like I was crazy but figured I just wanted some posters. I put those posters up in my room and kept pamphlets on my nightstand to read. My mom thought it was just a phase, but it grew into an aspiration. It wasn't about being a hero, though.

I just wanted to serve like they did. I wanted to do my part.

My father was strict. I was raised with six brothers on the poor side of Freeport, Texas. If you didn't fold the clothes right, my father would dump the whole stack and make you do it again. If you didn't wash the dishes correctly, he'd put them all back in the sink and you'd have to start over. When I enlisted in the Marine Corps after high school in 1991, the work ethic he taught me from an early age contributed to my success in moving up the ranks rather quickly.

My injury didn’t seem like a big deal at the time. In 1997, I was running and lost my footing and fell on my kneecap. I couldn't straighten my leg out, so the Marine Corps physician took an X-ray, but it didn't show any abnormalities. The doctors said I would be fine after a few days of icing, resting, and taking some medication. Unfortunately, that wasn’t the case.

When the pain didn’t subside, they put me on a four-week physical therapy program to reduce the inflammation and regain my range of motion. That, however, turned into 12 months, but my pain still wasn't getting any better. I didn't want more medication because it was making me sick, and I couldn't focus. Not one physician I saw thought to retake an X-ray. Eventually, they sent me to an orthopedic surgeon who performed an arthroscopic surgery in 1998 and reported there was nothing wrong with my knee or leg. I went back into physical therapy for another six weeks which turned into another 12 months.

At that point, two years after my injury, I started asking around about what else I could do and decided to go see a civilian orthopedic surgeon. He looked at my leg and immediately knew I had broken it. A new X-ray confirmed there was something wrong, and when he performed my second arthroscopic surgery, he discovered a fragment had broken off from my kneecap. Unfortunately, that fragment had torn all the cartilage over the years, so I was left with bone on bone.

In April 1999, I was honorably discharged from the Marine Corps because they weren’t able to find a solution for me to continue serving with my leg in the state that it was in.

My dream of being a career Marine was shattered.

Immediately after my honorable discharge, a third surgery was performed to reconstruct my knee. While in physical therapy, I continued to push forward taking on a new career in management and enrolling in college. Little did I know, an infection called osteomyelitis from that surgery was brewing.

By 2004, the chronic pain was intolerable, and the overwhelming feeling of hopelessness and lack of self-worth was mounting. While two infectious disease doctors were trying to find a solution for the infection, I was consumed with anger and bitterness toward the first surgeon who operated on me and hadn’t identified the problem from the start.

Eventually, I sought counseling to help deal with those emotions.

During that time, I went through a series of unsuccessful surgeries to remove the infection. By 2006, I was diagnosed with a major depressive disorder as well as an anxiety disorder due to being in chronic pain for nine years. By 2009, the infection had gotten so bad that the only solution was to amputate my leg above the knee.

After my amputation and a full year trying to fit into a prosthesis, the nerve pain was too great to continue. I gained so much weight and became borderline diabetic. I had always been a positive person when I was on active duty. No matter how challenging things got, I’d felt that my faith in God and myself was strong, but years of not exercising caught up with me, and I couldn’t stand looking at the person I saw in the mirror.

With each day, I mentally dug myself deeper into a dark hole.

By 2011, the Veterans Affairs doctors told me they couldn’t do anything more for me. After fourteen years of living with chronic pain and now, no medical intervention, I was completely lost and stuck in a “what if” mentality constantly dwelling on how things could have been if that first doctor had properly diagnosed my problem.

By 2013, my good leg became arthritic. My knee was weak, and I was prone to slips and falls while using my crutches. On a few occasions, I ended up in the emergency room due to hitting my head and limb. My wife kept telling me I needed to start using my wheelchair.

When I finally did, I wanted to exercise with her. She was a marathoner, and I wanted to enjoy the park like she did. I had gotten so out of shape that I was huffing and puffing after just a quarter mile in my chair. Four weeks after getting into my wheelchair, I decided to enter a 5k race despite people telling me I was crazy.

On race day, I discovered there was incline on the route. It just kept climbing and climbing. The last 100 feet of the race, I had to push my chair through soggy grass and mud. My shoulders were absolutely shot. When I crossed that finish line, a light went on. I thought if I could do that in the amount of pain and lack of shape I was in, then I can do anything. That was the beginning of my love of adaptive sports.

The competition aspect is part of my motivation to train. I was a runner before my injury, and although I never competed, I took great pride in consistently being among the top five Marines in my unit. I’m 5’7” and was barely 128 pounds in my early career, yet I was beating the 6’ tall, long-legged guys.

The other thing that motivates me to train is my wife. She ran my first race with me. She didn't want to see me in pain, so she kept telling me we should stop or that I should let her push me for a bit, but I wouldn’t let her.

I knew I could do it, and I wanted her to know that I could do things on my own.

I wanted to show her that she didn’t have to worry about me every day when she goes to work. That was the majority of my motivation.

I continue to compete in road and trail races, and I also discovered rowing a few years ago. In 2015, I attended the National Veterans Summer Sports Clinic in San Diego, which is a five-day event that introduces adaptive summer sports to disabled Veterans. We were at the Olympic Center learning the sport of rowing, and when I got off the water, a coach approached me and asked if I was interested in training to row competitively. They'd been looking for a male to partner up with a female to try to qualify for the Rio Paralympic Games. I laughed and told him I was ready to engage in any sport they’d pay for. He said the training camp would be covered, so we went up to the gym to do some testing on the erg. I was already in decent shape by then, and he thought I had potential and wanted to get me to camp.

Editor’s Note: An ‘erg’ is what rowers call an indoor rowing machine.

After the clinic, the coach sent me a two-a-day training regiment to follow for four weeks. I ended up dropping 23 pounds, putting on some muscle mass, and increasing my stamina. Just before going to camp, I had to go through a classification process to determine which category my disability fit into. Unfortunately, I was told the arthritis in my left leg wasn’t considered a disability which put me into a different classification than the one the coach originally thought I’d be in.

He wasn’t able to use me in Rio, but by then, I had caught the rowing bug.

Editor’s Note: Para-rowing, similar to other Paralympic sports, has several categories for competition based on the abilities of the athletes. For more information on para-rowing classifications, visit www.usrowing.org/para-rowing-classification-information.

My goal is to make the para-rowing national team for the 2024 Paralympic Games. I won’t make the 2020 team, unfortunately. In May, I learned that I had impingements in both shoulders, so I had to take some time off. Anybody with a medical condition knows that there are always setbacks. Every time I make a stride forward, it's often deviated by my condition. Chronic pain affects my mindset as well. For someone with a medical condition, having a positive attitude can only get you so far; you also need medical intervention. I'm not getting medical support from the VA, and that makes things more difficult. Luckily, I’m able to surround myself with positive people to help cope with it all.

My wife and brother, who’s an Air Force nurse practitioner, have always been concerned about me training for hours and hours and adding to my pain level which affects my sleep. They ask why I would do that to myself. I look at it this way: if I did no physical activity for an entire year, I would still have the same pain I have now. So why would I stop doing something that not only keeps me lean and healthy but also limits other future potential medical issues and gives me a sense of worth?

Before adaptive sports, I felt like I was worthless.

I couldn't even take out the trash or bring in the groceries without the fear of falling. Now, I’m capable of completing a 100-mile race, rowing nine miles, or doing a 1,000-meter sprint. That sense of accomplishment does wonders to your mindset. You feel so encouraged to go out there and do it all over again and share with others what exercise can do for them.

I have no qualms sharing that I was diagnosed with depression and an anxiety disorder. It is real for many people with medical issues. If people can know that I'm getting help for that while achieving what I have thus far, I hope that can help others in overcoming their struggles.

You don't have to do a 5k or even a mile. Just go out there and push your chair through a park, sit by the fountain, and listen to the kids laugh and play.

Find something you're passionate about.

Until you find that, wake up every day and type in “motivational speeches” on YouTube, and watch those videos. You'll hear different speakers, you'll see people doing awesome things, and you'll find the encouragement to get on with your day. If you can start with that, you will eventually find something you’re passionate about.

Editor's Note: All information contained in this article was extracted from communication with Bennie Jose Perez and USRowing.org.

About Amplitude

Amplitude Magazine provides valuable and unbiased news, information, and resources for amputees who want to live more fully, as well as articles and information relevant to their families and their caregivers. It offers content on a wide variety of topics, including peer support, active living, emotional issues, health and wellness, mobility, and adaptive living—anything that will help amputees enjoy all that life has to offer. Learn more at www.amplitude-media.com.

About the Author

Betsy Bailey has a diverse background including experience in marketing research at American Express, business operations and client relations with 601am, travel and culinary writing with VegDining, and playing volleyball professionally overseas.

Betsy has been writing for Wheel:Life since January of 2017 and thoroughly enjoys the process of getting to know her interviewees. She also teaches students learning English as a second language, speaks French fluently, and travels any chance she gets!